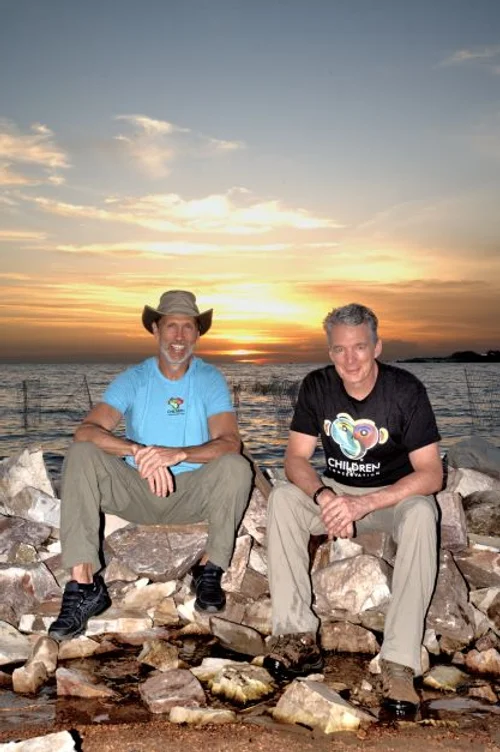

The story of Kerry Stumpe, Founder of not-for-profit organization Children of Conservation, alongside friend and board member Mike Thomas and their quest to save the disappearing shorelines of an orphaned chimpanzee island sanctuary.

Words by Lorna Campbell & Kerry Stumpe

Uniquely situated in East-Central Africa, Uganda is a virtual slideshow of the continents’ landscape and wildlife offerings. From its impenetrable rain forests, snow-peaked mountains, and sprawling savannahs to its glassy lakes; the ‘Pearl of Africa’ offers an extraordinarily diverse range of adventure. Most of its southern land mass is a sprawling shoreline married to the beautiful, but erratic, waters of Lake Victoria. As the largest tropical lake in the world, Victoria is often unyielding, unforgiving, and unpredictable. Thousands of tiny, seemingly insignificant, but populated islands splinter off the coast like shards of a broken glass bottle on the kitchen floor.

One of those superficially benign slivers is Ngamba Island. Just a short 45-minute boat ride south of Entebbe, this 100-acre island is the precious home to 50 orphaned chimpanzees as well as hundreds of species of vulnerable and endangered birds. While poaching of chimpanzees has declined over the years thanks to the Ugandan government and the Chimpanzee Sanctuary & Wildlife Conservation Trust that runs Ngamba; deforestation and illegal hunting for bushmeat and the pet trade remain a serious threat to human’s cousins.

Founded by Dr. Jane Goodall and a small group of conservationist pioneers, this one-of-a-kind primate sanctuary is divided into two sections. Ninety-eight acres of lush fruit and indigenous trees are dedicated for the chimps to forage and explore, while the remaining two acres are reserved for the island’s staff and a handful of lucky guests who can camp in one of four cottage tents at the water’s edge. Since chimpanzees don’t swim, there is no need for fencing on the shoreline. Once they leave their night enclosures for the day and disappear into the bush, they have the pleasure of a human-free existence without unnatural barriers, unlike any other chimp sanctuary in the world.

The case of the Chimpanzees in preserving Ngamba’s flora

When Ngamba was first designated as a new habitat for orphaned chimpanzees in 1998, experts projected that the island’s vegetation would be destroyed in less than 20 years. On the contrary, the presence of the chimps has actually resulted in an increase in plants and wildlife – not just in number, but diversity. You see, chimps are nature’s answer to a healthy rainforest ecosystem. They only eat the ripest fruits and berries, allowing flora to mature. When they move to different parts of the forest to settle each evening, they deposit richly fertilized seed pods along the way. As the forest density increases; more birds, bats, iguanas, otters, and other mobile animals start moving into “the best neighborhood in town” bringing their own “seed pods” from trees and plants on nearby islands where they feed for the day. This natural cycle continues to contribute to the diversity of plant species in their new home. In fact, since 1998, the diversity of flora and non-chimpanzee fauna on Ngamba Island has increased by almost 10%.

The biggest current challenge for this tiny island isn’t poaching or deforestation though – it’s water. At its peak, Ngamba only rises approximately 19 feet above Victoria’s edge, and, in the past 18 months, her water level has risen a record 5 feet. This unprecedented occurrence has claimed almost 30% of the Island’s precious shoreline. The rising waters have wreaked havoc at Ngamba and now pose a significant threat to the island and its endangered residents.

Children of Conservation and the Call to Save Ngamba Island

Kerry Stumpe, the founder of the non-profit, Children of Conservation, knows first-hand how important the rock and soil are that makeup Ngamba Island. For 9 years, Children of Conservation (“CofC”) has run a scholarship program providing an education for over 55 children of Ngamba’s staff, so Stumpe knows the island well. In December of 2020, Stumpe and fellow board member, Mike Thomas was meeting about a new CofC project when they got “the call” from Ngamba’s Executive Director asking for guidance on building a sea wall around critically eroded portions of the island.

Dr. Rukundo’s voice was solemn as he described the urgency of preserving what was left of the shoreline and rebuilding what had been lost. As the discussions advanced, it became clear that Stumpe’s background as an Architect and Thomas’s experience as a builder was going to be crucial to the project’s success. Ngamba could hire day laborers for the blocking and tackling but finding daily “on-site” managers to initiate the project and teach the laborers proper techniques for installation and stability had proven to be a challenge.

After a bit of research and several discussions with the Ngamba team, Stumpe and Thomas determined that this project would require the construction of a long gabion wall 30 feet from shore – a gabion being a galvanized metal cage filled with rock. The project would require hundreds of gabion cages (6 ft. long x 3 ft. wide x 3 ft. tall) that would be strategically joined together and positioned along the lake bottom perpendicular to the shore, filled with rocks hand-mined from a neighboring island to create a base/footing, then topped with another row of cages secured to the base but running parallel to the shore. It also became clear that the proper construction and placement of the gabions would be crucial to the long-term stability of the wall and the island itself.

The Diary of Kerry Stumpe

And so it began, as these Atlanta-based businessmen immediately started making plans to embark on a 12-day working adventure to save a little part of it the world. Although Stumpe had led other volunteer construction projects in Africa, this was Children of Conservation’s first endeavor to address the devastating effects of a natural disaster due to climate change. It was also the first project to be planned in the middle of COVID, which presented a host of logistical challenges. Intrigued by the unique nature of this project, laced with a new frontier in travel planning, Stumpe was to keep a journal of what would ultimately become an incredible wellness adventure, with entries that read…

“After enduring 2 COVID tests, 3 airports, a 4-hour layover in Amsterdam, 8-time zone changes, and 24 hours of travel time, all while being “masked up”, we arrive frazzled but excited in Entebbe, Uganda, shortly before midnight. We step off the plane and are immediately greeted by the fresh warm African breeze that wraps us up like a soft blanket on a snowy winter day. Until this moment, I had told myself that we were making the trip to help save Ngamba. However, being here suddenly makes us realize the impact the pandemic has had on our emotional well-being and we can already feel the gratitude that we know will be unavoidable as we spend the next two weeks side by side with guys who have faced unimaginable daily challenges their entire lives.

The airport is more desolate than usual, even for this time of night. COVID’s stranglehold on tourism stares us down as we coast through customs despite the added temperature checks, negative COVID test verifications, mandatory hand washing stops, and health screenings. It’s been a long day and it’s nice to see the familiar face of our driver as we walk out from the terminal.

In what seems to have only been minutes since I laid my head down on the pillow, daylight streams through the hotel curtains to welcome me to our journey. Before heading out, we grab a quick cup of joe (the coffee here is amazing) and a veggie egg omelet wrapped in chapatti (a local dish known as “Rolex”). Dr. Rukundo picks us up and leads us to several shoreline hotels where we inspect recent installations of the very same gabions, we will be using at Ngamba.

Our reconnaissance mission reveals an unthinkable amount of rock that will be required, and an even more sobering realization of the labor and hours it is going to take to install these “rock cages” without the use of any machinery. With no time to waste, we shuttle to the rustic boat dock at the marina. I’ve been here many times before but, despite having been told about the swelling of the lake, I’m in utter disbelief as I see the dock completely submerged. Just a year ago, there was nearly 5 feet of clearance between the top of the water and the dock. Now, I’m wishing I’d unpacked my waders as our tennis shoe-clad feet become immersed, tiptoeing through the water-covered wood to the small single-engine boat.

Our Captain carefully disembarks, and I turn for the first time to look back at the familiar shoreline. What used to be a desirable and growing waterfront is now littered with flooded and abandoned buildings that slowly disappear as we turn southeast and begin navigating the choppy waters of Lake Victoria. Fifteen minutes into the trip, the Captain shuts off the engine and stops. He announces in a heavy Ugandan accent “We are now sitting on the Equator.” Maybe it’s just the small-town boy from the Midwest in me, but no matter how many times I make this trip, I never get tired of the notion that I’m crossing the Equator, surrounded by ocean-like waves in a lake that’s bigger than the state of West Virginia!

As we approach Ngamba, her visual profile stands out amongst her sister islands. While the others have been scraped bare by human habitation, Ngamba is a beautiful sight of dense dark green vegetation. There’s a small patch of land with 7 visible and distinct structures: the dining pavilion, a welcome center, an education building, and 4 visitors’ tents. I think back to my first trip here over 10 years ago. I have fond memories of laying with my wife on the platform deck of our tent amazed by the endless stars in the night sky. Our old tent is gone, and that platform is now underwater. The new semi-permanent tents that were erected just 3 years ago and 30 feet inland are now alarmingly close (if not partially engaged) with the rising waters. Nonetheless, the sight of these open-air buildings with thatched cones and hipped roofs is welcoming and our excitement is palpable. As we make landfall, we are once again reminded of the power of Mother Nature. The dock that was here just last year has also been swallowed by Victoria and now serves solely as an underwater base for the newly constructed makeshift dock that we use to disembark.

We were expecting to stay in the rudimentary staff quarters with shared showers and toilets, but the COVID-related tourism restrictions have rendered all the guest tents vacant. We’re pleasantly surprised to learn that we’ll each be spending our next 2 weeks in our own private roomy and comfortable thatch-roofed abodes with solar-heated water for showers and perfectly functional (private) indoor plumbing for sinks and toilets. Our old friend, Rashida, welcomes us and reminds us to ALWAYS close our doors. Open doors are billboard-sized invitations to any one of the tens of thousands of fruit bats that migrate nightly at dusk, not to mention the friendly 6-foot iguanas that live beneath our lakefront homes. There is, however, little concern as our reptilian friends are super shy and scurry from us every time we approach! We spend the rest of the day taking stock of materials, assessing the project, and meeting about the daunting challenge that lies ahead. We sleep well, surrounded by the sounds of nature, and are awoken by the excited pant hoots of happy chimpanzees anticipating their morning feeding.”

The mission of the mind to project execution

Stumpe continues…

“There just seems to be more daylight at the equator. Days start early and end late when working manual labor. Our typical day starts at 6:30 am with coffee and tea in the dining hall where we sit, mesmerized by the intoxicating waves lapping along Victoria’s edge. Work begins promptly at 7 and breakfast is served at 9:30 (like all guest meals, it is prepared to order). Yes, if you are a laborer in Uganda, you work BEFORE you eat.

Our crew is a rag-tag group of 5 hard-working twenty-something Ugandan men from the capital city of Kampala; 4 more will join us next week. They are dressed in an array of denim jeans and work pants with old t-shirts and polos. We soon discover that they will wear the same clothes every day of our project. Some have boots and gloves while others are without. Mike came well prepared but has now given his extra sets of gloves to 2 of the workers who worked with none. As I look at their strong rugged hands, I find myself wondering if they would even know the difference. I’ve always considered myself a pretty tough nut, but these guys take it to a whole other level. Donned in our new “work” gear that Mike and I had the “privilege” of ordering online and delivered to our doorsteps before we left, it’s time to get moving.

There are numerous stacks of caging material piled around the yard. To some, the piles would appear to be nothing more than masses of metal, but we know that these soon-to-be-constructed gabions represent a beacon of hope for the island. The crew carefully connect, twist, and secure the mesh grid panels with heavy gauge wires and pliers to form individual cages. They systematically join six cages at a time into a slightly semicircular bundle that will ultimately result in a serpentine design. From this point forward, the building of the cages will be tackled in the evenings, as a way to rest while still moving ahead on the project after the day’s heavy lifting of rocks. It will prove to be a slow, but steady process as our small crew can only move so many stones in any given day.

Once the first few bundles are connected, we each grab a section. As if we are carrying nitroglycerin in a James Bond film, we carefully walk the bound, empty cages in unison into the warm uneasy waters. Most mornings, the temperature is a pleasant 60-70 degrees and, since we are working on the western side of the island, we spend the first couple of hours in the shade. We place the bundles about 30 ft. from the shore and position them on Victoria’s sandy bottom, securing them from the possible undertow. We choreograph our work with Mother Nature’s dance and use her waters as a level. We create a sturdy foundation base that tops out 6 inches below the waterline. The placement of these foundation cages is crucial as, once they are filled, additional cages will be placed on top running parallel to the shore. This top layer will create a visible band several feet above the lake, slithering in continuous “s” curves like our shy iguanas swimming in the clear waters. Eventually, the 30-foot space between the shore and our gabion wall will be backfilled and planted to re-establish the washed-out soil and rebuild the island.

While challenging, and definitely the most crucial part of the project, placing the gabions is a welcome task compared to the unceremonious and laborious work of filling them with rock. Unlike the modern conveniences of home, there is no Home Depot or Lowes to call for a delivery. The rock we are using is being hand-mined daily, with pickaxes and sledgehammers, by a crew of a dozen men that could easily be mistaken for pirates, from the neighboring island of Kome. They deliver our bootie twice a day on two overloaded 25 ft. beat-up boats and toss the stone on the shore. We inquire if our “pirate” friends could, perhaps, unload the rocks directly into the cages (30 feet from shore and easily accessible by

their boats) to save us the labor of transferring the rocks manually, but the captain of the crew is on a “schedule” and will not alter his plan to assist in helping our cause. Of course, this lack of “construction courtesy” is not unique to Africa, as we’ve experienced the same familiar attitude on virtually every project we’ve ever worked on in the U.S.

Given the positioning of the rock piles on the shore, we create a human chain, like firemen with water buckets, moving the stones one by one to the gabions that now seem a mile away. It is an “all hands on deck” effort with our crew, us, and even Dr. Rukundo, thigh-deep in the water wearing his dress khakis for work. The water is chest high for the four guys at the end who carefully place each stone in the baskets. Cross wires must be installed every 8 inches to stabilize and secure the cage sides from buckling. The cages are completely submerged below the water’s surface so the crew takes turns holding their breath and plunging beneath the waves to make it happen. Thankfully, this process means the crossties take several minutes, which allows our 55-year-old backs a much-needed rest fairly often.”

Days of impact and nights of beauty continue

“Day two promises to be a repeat of day one; except that our pirate captain actually does seem to have the capacity for empathy as he arrives with 2 incredibly old and very leaky wooden canoes to serve as our “rock caddies” for the remainder of our construction adventure. Each boat can hold approximately 200 lbs. of stone. Despite having to dedicate one of our crew full time to “bailing water” from the porous boats, being able to load them at the shore and unload them into the gabions is proving to be much more efficient than our human chain gang. As the days begin to meld together, our crew becomes more capable and more confident.

Days become nights and the nights here are unlike any I’ve ever experienced. Dusk is my favorite time on the island, as we sit and enjoy the symphony around us. There’s a soft and almost imperceptible buzz in the air as thousands of fruit bats voyage away from the island for their nightly feeding, while hundreds of white (and not so quiet) egrets migrate in, covering the trees for the night’s slumber-like freshly fallen snowflakes. The chimps begin to emerge from the forest, shrieking with joy as they enter their night-time lodging in anticipation of their evening porridge. This treat is not only a delicious snack, but it allows the staff to ensure the chimps get extra nutrients or medications they might need. As the sun sets on the horizon, the vastness of the sky reveals itself and the darkness becomes alive with majestically clear and unthinkable views of the Milky Way. From our porches, we can hear the rhythmic sound of gentle waves that dissolve into the makeshift rock shoreline, and a steady breeze flutters our tent flaps. We look out over the black horizon and notice what appears to be fireflies dancing on the lake in the distance. Upon closer examination, we see that the fluttering lights are actually the rustic incandescent lamps of a hundred or so night fishermen that arrive shortly after sunset and remain until daybreak.

Throughout the week, we measure each day’s success linearly as our efforts are on full display under the clear waters like a ship in a bottle. The chimpanzee keepers have become our cheerleaders, stopping by occasionally to see the project with encouraging words and disbelief. For them, the construction of this wall serves as a hopeful and certainly, positive step forward, in the long string of despair they have faced this past year. Like almost everyone else, this global pandemic has left many in their communities jobless and threatened the lives of their families and friends. However, unlike us, they live in a country where approximately 65% of the population was already living below or just above the poverty line. In addition, the shutdown has restricted visitors to the island, cutting off the much-needed revenue to feed and care for their hairy orphaned friends. Due to COVID and the risk of transmission to the chimps, the staff is now enduring the grind of a mandated skeleton crew that works an isolated 15-day on, 15-day off work schedule. These struggles have been magnified by the flood waters from Victoria and the gut-wrenching sight of watching their precious island disappear slowly into her grasp. Seeing the glimmer of joy and hope in the eyes of our colleagues, we could not be happier to be a small part of the master plan to rebuild and restore the island for ALL her inhabitants.

The continuous sounds of nature bring everything into constant perspective. Whether it be the chirp and chatter of the lapwings and weaver birds, the occasional hoots of the chimpanzees playing in the forest or the waters gently splashing against our legs and aching forearms; we are constantly reminded of the simplistic beauty that surrounds us. Mike and I have decided that, if there is a laborer’s heaven – this surely must be it. On the other hand, the very shoreline we are working to restore demonstrates the power of Mother Nature and the devastating impact of climate change. This project also serves as a lesson in humanity and the importance of partnerships and working together. We work side by side with our local crew and the staff at Ngamba, rely on the crucial rocks provided by the residents of Kome Island, and collaborate with the Ugandan government to preserve this place of national heritage – each an important part of the whole – each benefiting from the partnership with the other.”

Celebrating critical milestones

Stumpe concludes…

“By the end of our stay, we’ve taught the local crew the technical aspects and skills to ensure the proper installation of the gabions. Our hands-on approach means we will leave having completed 300 ft. of the wall which, when complete, will remain a visible and constant reminder of Victoria’s wrath of 2020. We have constructed and installed 52 gabion cages and moved over 200,000 lbs. of stone, but this is just the beginning. We are genuinely humbled and impressed with our crew. They are the hardest-working young men you will ever find and have an estimated 5 more weeks of work to complete their portion of the project. As for our pirates, they will continue to work for another 3 months to complete the backfill of our structure. With any luck at all, the dock, and shoreline of this critical part of the Island will be restored completely by July, just in time to be on the other side of the COVID pandemic and begin welcoming tourists back to this magically unique place.

There’s an African proverb that says, ‘If you ever think you’re too small to make a difference, spend the night in a closed room with a mosquito.’ As we head back home to face the second year of COVID, intermixed with heated political rants broadcasted endlessly throughout every media outlet, it will be natural to feel small and defeated by the “next” bad thing that may come our way. But we can now accept our broken world, having been given the greatest gift of all, over the past 12 amazing days. We got to be mosquitos – small (and a bit pesky to our hard-working crew), but able to make a difference – to serve a purpose much greater than ourselves – and to do so in one of the most wonderful places on the planet.”